Irish Whiskey is my least favorite category of whiskey.

To be fair that’s only because I think about Canadian Whisky so infrequently that I genuinely forget that it’s a thing. Yet, there are some true gems in the category. Redbreast should be a staple at any bar. Tyrconnell Madeira Cask is one of my favorites bottles of any category, and I can’t count the number of shots of Power’s I’ve had. The problem is that these don’t define the category of Irish Whiskey. Accounting for 82% of sales in the United States Jameson’s Irish Whiskey is essentially the entire category of Irish Whiskey. And Jameson’s just isn’t for me.

Call me elitist, I’m sure part of my distaste for Jameson is it’s ubiquity, but it isn’t very interesting to me. It’s light, forgettable and honestly a little harsh. And while I might love the aforementioned bottles the first two aren’t affordable mixers and trying to convince a Jameson drinker to have a dram of Power’s instead is a lesson in futility. People aren’t cold calling high end Irish whiskey the way they are Japanese, Scotch, or Bourbon so it becomes an afterthought. Which brings me to Bushmill’s.

I got a call from friends at Half Full, The Daily Beast’s Food and Drink section, asking me what I thought about Bushmills. And my answer was, “I honestly haven’t thought about it in a while.” They then asked if I’d be interested in coming on a trip to film a documentary and explore Bushmill’s and I said of course because who doesn’t want an excuse to go to Ireland?

But beyond the boondoggle of a trip there was a genuine curiosity. Irish Whiskey is currently the fastest growing spirit category in the world. The industry went from a measly four distilleries on the whole island in 2013 to 16 distilleries in production today with another 13 on the way. While these numbers pale in comparison to the sales and production numbers of Scotch and Bourbon clearly many people with a lot of money feel that this is not just single brand growth but a reemerging category. I wanted to see what was giving these people such confidence.

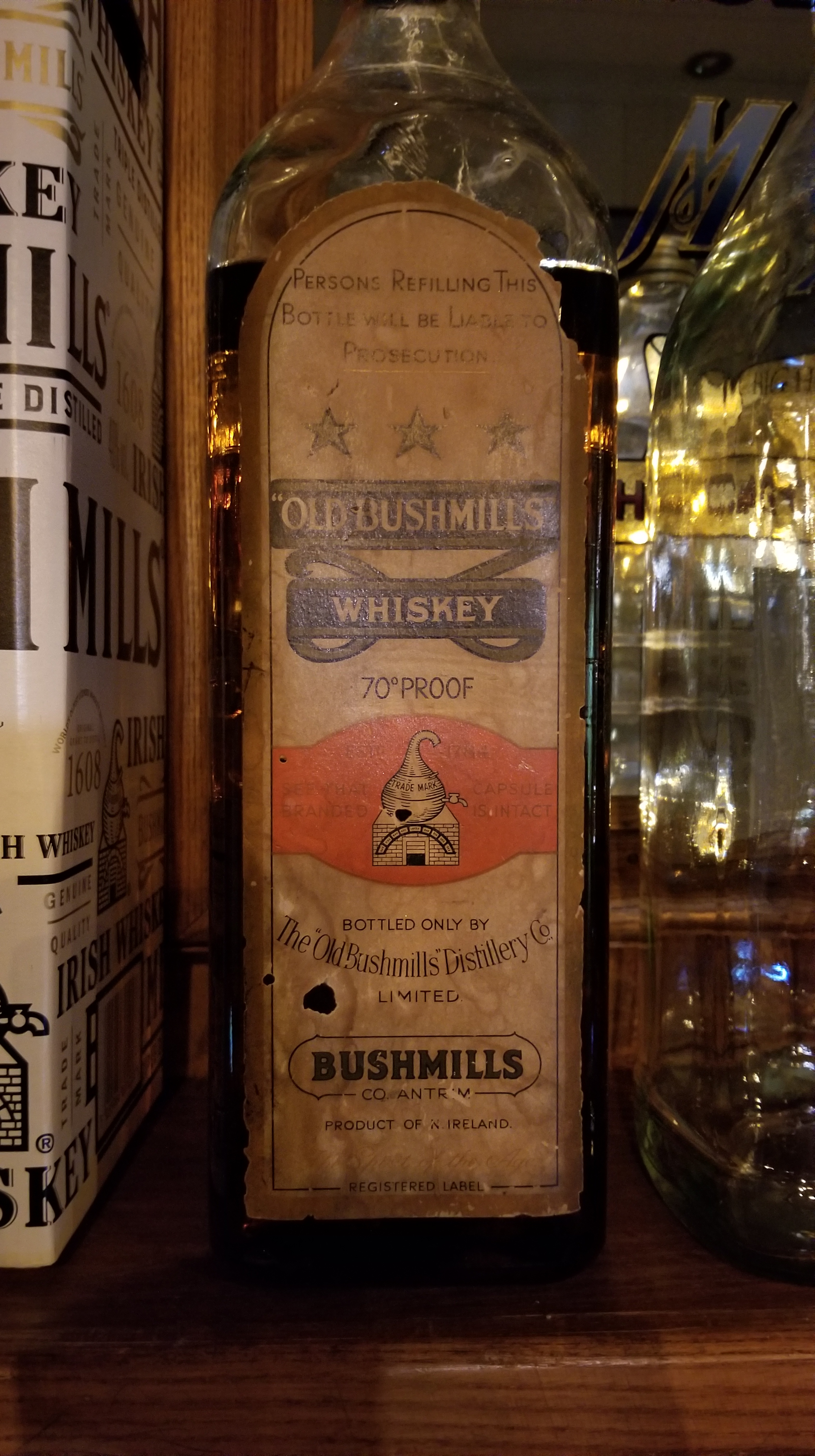

We spent two days at the Old Bushmills Distillery and the surrounding countryside. The distillery takes its name from the River Bush and all the water used on site comes from the rivers tribute Saint Columb’s Rill. Although the date 1608, the year King James I granted a writ to distill whiskey to Sir Thomas Philips, is emblazoned everywhere, the Bushmill’s Old Distilling Company wasn’t establish until 1784. No matter which date you take as the distillery’s origin Old Bushmill’s is the only distillery in all of Ireland that was in operation before 1974 and was one of the three that kept production alive.

Irish Whiskey has always been deeply tied to the American market and American Prohibition tanked the industry. 400 brands made by over 160 distilleries became three distilleries all owned and operated by a single group, Irish Distillers, with their purchase of Bushmill’s in 1972. Irish Distillers was purchased by Pernod Ricard in 1988 with Bushmill’s then purchased by Diageo in 2005. They began a massive ad campaign to gain market share but even the largest liquor company in the world couldn’t seem to boost the brand and it was sold to Jose Cuervo in 2014 after Bushmill’s sold 1.3 million liter cases in the U.S. compared to Jameson’s 18 million.

Everyone loves a good underdog story and while technically being in second place Bushmill’s was a very clear underdog. A part of me was hoping I’d find some spark that craft spirit authenticity or other such nonsense that would make it worth the uphill battle to recommend Bushmill’s White Label over Jameson’s iconic green bottle. What I found out is that the White label isn’t what you should be drinking.

Bushmill’s is a single malt distillery. They age grain whiskey on site for blending but every drop of whiskey that’s distilled at the distillery is Irish Single Malt. This is unusual because most non-blended Irish whiskey is Single Pot Still, which is a distillate made up of both Malted and Unmalted Barley. This style originated as a middle finger to the English who put a tax on malted barley in 1785. Despite the added expense Bushmill’s has only ever made Single Malt.

Irish Single Malt is also distinct from (most) Scotch Single Malt in that it is triple distilled instead of double distilled. This creates a lighter whiskey as it’s gone through an additional set of cuts and stripping. This malt forms the base of all of the blends and single malt line at Bushmill’s . And every bottle of Bushmill’s is put together by the first female master Blender in all of Irish Whiskey history. She’s sitting comfortable with over 25 years of experience tripping across her palette and when she proclaims the 10 year old single malt to be her personal favorite there’s a weight that goes along with that statement.

The 10 Year Old fills a very interesting place for Irish Whiskey. It’s affordable, mixable, and quaffable on it’s own it could honestly be that missing midpoint for Irish whiskey that bridges the shots and the Super Premium category. Yet from what I tasted it the true gem of the line is the 16 Year old Single Malt.

Aged for a minimum of 16 years a blend of ex-Bourbon and Olorosso barrel aged single malt is blended together and then further aged for an additional 6 months in used port barrels. It was the first thing I was poured after nearly 18 hours of travel and was one of those moments of surprise and disbelief at how good it was. In conversation with Noah Rothbaum, Senior Editor at Half Full, he expressed how it reminded him of the experience of discovering Hibiki 12 years ago before we drank it all-I had to agree with him. But not trusting my jetlagged senses I proceed drink at least a bottle over the next few days and to bring a bottle home for continued research.

NOSE: Dark Fruit, Raisin, Plum, and a touch of vanilla.

PALETTE: Dried Red Fruit, a slightly nutty undertone with a bright sherry through line to cut through the toffee, vanilla, and richness of the malt.

FINISH: Long and lingering, leaving the dried fruit and a slight amount of tannin and spice.

Ultimately I came away from Bushmill’s, and Ireland, with another story. A spirit is ultimately the distillation of the people who make it. A distillation of their culture, their taste, their landscape, and their time. Getting to know them, getting to experience them, ultimately opens doors to experience a spirit they way they do. In the end, Jameson is still my least favorite Irish Whiskey but, like life, whiskey is really shades of grey. A single dominant force can not define either.