Bigger is always better right? Just like the old fashioned way is the best way. Or at least that’s what Aberlour has been banking on the past two decades with their A’bunadh releases.

Despite a history stretching back nearly 140 years Aberlour still feels relatively unknown to the wider world. The distillery was founded in 1879 by James Fleming who built an extremely modern distillery for the time powered by a waterwheel driven by the Lour river . Aberlour literally means “the mouth of the chattering burn” and was supposedly named for the ancient Druids belief that the river actually spoke to them. The water for the distillery is drawn from St. Drostan’s Well, which only adds to the mythic nature of the Aberlour’s waters as the well is named after the 6th century Columbian Monk who supposedly used it as a baptismal site. So, like many Scotch distilleries there is a lot of history, myth, and legend involved.

James Fleming operated the distillery until his death 1895 and then the distillery changed hands over the years, being acquired by S. Campbell & Sons in 1945, before being sold to Pernod Ricard in 1974, who updated and expanded the distillery the following year, finally merging the former Campbell Distilleries with the Chivas Brothers in 2001.

Aberlour is quintessentially Speyside in style and is double cask matured. Unlike the more well known Balvenie line, the Aberlour line isn’t finished in a second style of oak. Instead, the malt is fully matured in ex-bourbon or Olorosso Sherry barrels and once they are finished aging these different barrel styles are batched together. The proportion varies depending on the interation. The 12 Year is 75% Ex-Bourbon, the 16 year is 50/50, and the A’bunadh is 100% Sherry. And while the general line up of Aberlour might be less known the A’bunadh definitely has a cult following. Though it was first released in 2000 the A’bunadh story actually begins with that distillery expansion brought on by their purchase by Pernod Ricard in 1975.

During construction some workers stumbled upon some an 1898 newspaper with a story about the distillery fire that year, wrapped around a bottle of Aberlour from 1898. The workers who discovered the bottle finished off most of the bottle before guilt kicked in and they turned the bottle over to the master distiller, who immediately sent the remainder off to the laboratory for analysis. The A’bunadh is an attempt to recreate the whiskey in that bottle.

“A’bunadh” means “the original” in Gaelicand if the above story is to be believed this is the style of malt the distillery was making before it’s catastrophic fire in the late 1900s. There is no age statement, each batch is blended together from malts ranging from 5 – 25 years old, is non chill filtered, and bottled at cask strength. It is 100% Olorosso Sherry barrel aged and though there is no age statement , each batch is uniquely numbered allowing whiskey connoisseurs, otherwise known as nerds, to easily track the “best” batches.

2017 saw the release of Batch 58 but I’ve still got a few bottles of the 57 hanging around and it lives up to its predecessors. There is a massive amount of all spice and caramelized orange on the nose. There is a massive amount of that Sherry sweetness, melded with orange, dark fruit, a little bitter chocolate and heavy malt. The finish is long and sustained and with Batch 57 coming in at solid 11.42 proof the mouth is left dry and clean afterwards.

Whether or not the A’bunadh actually is like the original malt distilled at Aberlour is rather irrelevant at this point. It has certainly earned its place in the Single Malt hierarchy and deserves a little more love from those of us not constantly dreaming about our next dram.

The cynic in me wants to say that the whole ‘unique experience’ is marketing talk for ‘we can’t get the ingredients to make this anymore.’ That it’s just another way to cash in on the whiskey boom. But looking at how long Don and Willie have been doing this it looks more like to men tired of doing the same thing day in and day out. It has the feel of wanting to find something new, to experience and share it. So what does the millennial in me say? That it’s not a generational thing. That it’s just a human thing.

The cynic in me wants to say that the whole ‘unique experience’ is marketing talk for ‘we can’t get the ingredients to make this anymore.’ That it’s just another way to cash in on the whiskey boom. But looking at how long Don and Willie have been doing this it looks more like to men tired of doing the same thing day in and day out. It has the feel of wanting to find something new, to experience and share it. So what does the millennial in me say? That it’s not a generational thing. That it’s just a human thing.

of the spirit.

of the spirit.

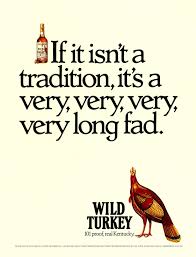

y as a brand was said to originate in the 1940’s when an Austin Nichols executive, Thomas McCarthy, brought some choice whiskey along on a wild turkey hunting trip in South Carolina. Enamored with the samples he brought his friends kept asking for more of “that wild turkey bourbon.” More likely it was a marketing approach to appeal to hunters and the rugged, rustic type but every whiskey loves a mythical origin story.

y as a brand was said to originate in the 1940’s when an Austin Nichols executive, Thomas McCarthy, brought some choice whiskey along on a wild turkey hunting trip in South Carolina. Enamored with the samples he brought his friends kept asking for more of “that wild turkey bourbon.” More likely it was a marketing approach to appeal to hunters and the rugged, rustic type but every whiskey loves a mythical origin story.

The whiskey produced at McKenna’s Nelson County distillery never carried the name ‘Bourbon’ but it was regarded to be of the highest quality. Newspaper at the time noted that McKenna never sold a drop that wasn’t at least three years old. There was even a bill introduced to Congress in 1892 asking for unlimited bond period on aging whiskey to prevent tax penalties on whiskey aging beyond the bond. This bill was known as “The McKenna Bill.” The next year McKenna passed away at the age of 75.

The whiskey produced at McKenna’s Nelson County distillery never carried the name ‘Bourbon’ but it was regarded to be of the highest quality. Newspaper at the time noted that McKenna never sold a drop that wasn’t at least three years old. There was even a bill introduced to Congress in 1892 asking for unlimited bond period on aging whiskey to prevent tax penalties on whiskey aging beyond the bond. This bill was known as “The McKenna Bill.” The next year McKenna passed away at the age of 75.