Bigger is always better right? Just like the old fashioned way is the best way. Or at least that’s what Aberlour has been banking on the past two decades with their A’bunadh releases.

Despite a history stretching back nearly 140 years Aberlour still feels relatively unknown to the wider world. The distillery was founded in 1879 by James Fleming who built an extremely modern distillery for the time powered by a waterwheel driven by the Lour river . Aberlour literally means “the mouth of the chattering burn” and was supposedly named for the ancient Druids belief that the river actually spoke to them. The water for the distillery is drawn from St. Drostan’s Well, which only adds to the mythic nature of the Aberlour’s waters as the well is named after the 6th century Columbian Monk who supposedly used it as a baptismal site. So, like many Scotch distilleries there is a lot of history, myth, and legend involved.

James Fleming operated the distillery until his death 1895 and then the distillery changed hands over the years, being acquired by S. Campbell & Sons in 1945, before being sold to Pernod Ricard in 1974, who updated and expanded the distillery the following year, finally merging the former Campbell Distilleries with the Chivas Brothers in 2001.

Aberlour is quintessentially Speyside in style and is double cask matured. Unlike the more well known Balvenie line, the Aberlour line isn’t finished in a second style of oak. Instead, the malt is fully matured in ex-bourbon or Olorosso Sherry barrels and once they are finished aging these different barrel styles are batched together. The proportion varies depending on the interation. The 12 Year is 75% Ex-Bourbon, the 16 year is 50/50, and the A’bunadh is 100% Sherry. And while the general line up of Aberlour might be less known the A’bunadh definitely has a cult following. Though it was first released in 2000 the A’bunadh story actually begins with that distillery expansion brought on by their purchase by Pernod Ricard in 1975.

During construction some workers stumbled upon some an 1898 newspaper with a story about the distillery fire that year, wrapped around a bottle of Aberlour from 1898. The workers who discovered the bottle finished off most of the bottle before guilt kicked in and they turned the bottle over to the master distiller, who immediately sent the remainder off to the laboratory for analysis. The A’bunadh is an attempt to recreate the whiskey in that bottle.

“A’bunadh” means “the original” in Gaelicand if the above story is to be believed this is the style of malt the distillery was making before it’s catastrophic fire in the late 1900s. There is no age statement, each batch is blended together from malts ranging from 5 – 25 years old, is non chill filtered, and bottled at cask strength. It is 100% Olorosso Sherry barrel aged and though there is no age statement , each batch is uniquely numbered allowing whiskey connoisseurs, otherwise known as nerds, to easily track the “best” batches.

2017 saw the release of Batch 58 but I’ve still got a few bottles of the 57 hanging around and it lives up to its predecessors. There is a massive amount of all spice and caramelized orange on the nose. There is a massive amount of that Sherry sweetness, melded with orange, dark fruit, a little bitter chocolate and heavy malt. The finish is long and sustained and with Batch 57 coming in at solid 11.42 proof the mouth is left dry and clean afterwards.

Whether or not the A’bunadh actually is like the original malt distilled at Aberlour is rather irrelevant at this point. It has certainly earned its place in the Single Malt hierarchy and deserves a little more love from those of us not constantly dreaming about our next dram.

of the spirit.

of the spirit.

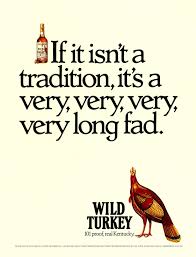

y as a brand was said to originate in the 1940’s when an Austin Nichols executive, Thomas McCarthy, brought some choice whiskey along on a wild turkey hunting trip in South Carolina. Enamored with the samples he brought his friends kept asking for more of “that wild turkey bourbon.” More likely it was a marketing approach to appeal to hunters and the rugged, rustic type but every whiskey loves a mythical origin story.

y as a brand was said to originate in the 1940’s when an Austin Nichols executive, Thomas McCarthy, brought some choice whiskey along on a wild turkey hunting trip in South Carolina. Enamored with the samples he brought his friends kept asking for more of “that wild turkey bourbon.” More likely it was a marketing approach to appeal to hunters and the rugged, rustic type but every whiskey loves a mythical origin story.

The whiskey produced at McKenna’s Nelson County distillery never carried the name ‘Bourbon’ but it was regarded to be of the highest quality. Newspaper at the time noted that McKenna never sold a drop that wasn’t at least three years old. There was even a bill introduced to Congress in 1892 asking for unlimited bond period on aging whiskey to prevent tax penalties on whiskey aging beyond the bond. This bill was known as “The McKenna Bill.” The next year McKenna passed away at the age of 75.

The whiskey produced at McKenna’s Nelson County distillery never carried the name ‘Bourbon’ but it was regarded to be of the highest quality. Newspaper at the time noted that McKenna never sold a drop that wasn’t at least three years old. There was even a bill introduced to Congress in 1892 asking for unlimited bond period on aging whiskey to prevent tax penalties on whiskey aging beyond the bond. This bill was known as “The McKenna Bill.” The next year McKenna passed away at the age of 75.

But in a world of vanishing age statements and soaring prices I feel it’s hard for the general consumer to not see this as a replacement of a beloved bottle by a younger whiskey at a higher price. That’s not a problem with the Harmony though. That’s just the reality of the whiskey world we now live in.

But in a world of vanishing age statements and soaring prices I feel it’s hard for the general consumer to not see this as a replacement of a beloved bottle by a younger whiskey at a higher price. That’s not a problem with the Harmony though. That’s just the reality of the whiskey world we now live in.

nown as the Boulevard Distillery) in 1971 and renamed it the Wild Turkey Distillery. This purchase made sense since the Ripy distillery was where most of the Wild Turkey Whiskey was coming from but it was terrible timing as “white goods” started gaining steam and the bourbon market tanked. The brand and distillery, were purchased by Pernod Ricard in 1980 and then sold to Gruppo Campari in 2009. But through out all of those changes Jimmy Russell has been there, making whiskey.

nown as the Boulevard Distillery) in 1971 and renamed it the Wild Turkey Distillery. This purchase made sense since the Ripy distillery was where most of the Wild Turkey Whiskey was coming from but it was terrible timing as “white goods” started gaining steam and the bourbon market tanked. The brand and distillery, were purchased by Pernod Ricard in 1980 and then sold to Gruppo Campari in 2009. But through out all of those changes Jimmy Russell has been there, making whiskey.

ake anymore? Seeing the Wild Turkey 101 Rye return with a vengeance was transcendent moment amidst all of these brands lowering proof and dropping age statements. Yet for all of my love of Jimmy, and his rye, when I drink the Bourbon it’s usually me trying to figure out why I don’t drink the Bourbon.

ake anymore? Seeing the Wild Turkey 101 Rye return with a vengeance was transcendent moment amidst all of these brands lowering proof and dropping age statements. Yet for all of my love of Jimmy, and his rye, when I drink the Bourbon it’s usually me trying to figure out why I don’t drink the Bourbon.

Let me explain. Despite not carrying standard Woodford I’ve always been interested in the Master’s Collection (and the rye but that’s a story for another time). The Master’s Collection is an ongoing series that first began in 2005. It is a once a year release that is always something experimental. It doesn’t always qualify as a bourbon, the mashbill might not meet the required limits or the barrel finishes might be outside the strict bourbon law, but they are always ambitious. And more interestingly they are supposedly whiskey produced only from the pot stills at the prime Woodford Distillery in Versailles, KY.

Let me explain. Despite not carrying standard Woodford I’ve always been interested in the Master’s Collection (and the rye but that’s a story for another time). The Master’s Collection is an ongoing series that first began in 2005. It is a once a year release that is always something experimental. It doesn’t always qualify as a bourbon, the mashbill might not meet the required limits or the barrel finishes might be outside the strict bourbon law, but they are always ambitious. And more interestingly they are supposedly whiskey produced only from the pot stills at the prime Woodford Distillery in Versailles, KY. I’m in love with the idea of all of these yet on the actual liquid hasn’t always lived up to those expectations. But those expectations aren’t always fair. The Woodford name can sometimes influence what you expect to be tasting. For instance, Brown-Forman used to distill the Rittenhouse Rye for Heaven Hill while their production was limited due to a distillery fire in the 90’s. Yet once Heaven Hill moved production back to their own distillery and Woodford released a rye that is pretty obviously a continuation of that Rittenhouse heritage I judged it more harshly simply because of that Woodford name.

I’m in love with the idea of all of these yet on the actual liquid hasn’t always lived up to those expectations. But those expectations aren’t always fair. The Woodford name can sometimes influence what you expect to be tasting. For instance, Brown-Forman used to distill the Rittenhouse Rye for Heaven Hill while their production was limited due to a distillery fire in the 90’s. Yet once Heaven Hill moved production back to their own distillery and Woodford released a rye that is pretty obviously a continuation of that Rittenhouse heritage I judged it more harshly simply because of that Woodford name.

Named after the stream that ran along Abraham Lincoln’s childhood home in Kentucky, the bottle was modeled after turn of the century apothecary bottles with the label inspired by the tradition of wrapping bottles in newspaper at the distillery. Knob Creek was originally an age stated 9 Year Old bourbon bottled at 100 proof. The age statement has been dropped in the past few years but the brand still claims extra aging compared to the companies other small batch whiskies. So in this case pre-Prohibition style would seem to mean longer aged and higher proof, which is almost the exact opposite of what those early whiskies would have been.

Named after the stream that ran along Abraham Lincoln’s childhood home in Kentucky, the bottle was modeled after turn of the century apothecary bottles with the label inspired by the tradition of wrapping bottles in newspaper at the distillery. Knob Creek was originally an age stated 9 Year Old bourbon bottled at 100 proof. The age statement has been dropped in the past few years but the brand still claims extra aging compared to the companies other small batch whiskies. So in this case pre-Prohibition style would seem to mean longer aged and higher proof, which is almost the exact opposite of what those early whiskies would have been. What set the Booker’s Rye apart was the age and a unique mashbill. The Knob Creek 2001 certainly has the age, at 14 years old it clocks in a good five years older than the old 9 year, but there’s no variation on the mashbill, simply different batches. This leaves a through line connecting it to the standard issue Knob Creek because no matter what batch you pick up all of these bottles are unmistakably Knob Creek: powerful, with pistachio, walnut, sweet oak and that unmistakable Jim Beam yeast.

What set the Booker’s Rye apart was the age and a unique mashbill. The Knob Creek 2001 certainly has the age, at 14 years old it clocks in a good five years older than the old 9 year, but there’s no variation on the mashbill, simply different batches. This leaves a through line connecting it to the standard issue Knob Creek because no matter what batch you pick up all of these bottles are unmistakably Knob Creek: powerful, with pistachio, walnut, sweet oak and that unmistakable Jim Beam yeast.

have that in common. But unlike myself Burns pursued poetry, and love, with uncommon zeal. The first collection of his poems was published by subscription in 1786. While writing most of these poems in 1785 he also fathered the first of his 14 children. He was a busy man. As his biographer DeLancey Ferguson said of him, “it was not so much that he was conspicuously sinful as that he sinned conspicuously.”

have that in common. But unlike myself Burns pursued poetry, and love, with uncommon zeal. The first collection of his poems was published by subscription in 1786. While writing most of these poems in 1785 he also fathered the first of his 14 children. He was a busy man. As his biographer DeLancey Ferguson said of him, “it was not so much that he was conspicuously sinful as that he sinned conspicuously.” Ninety years later, on the opposite side of Scotland, another farmer was setting out to form his own legacy in a distinctly Scottish way: by quitting his job. William Grant had just quit his job as a bookkeeper at the Mortlach Distillery and purchased the land and equipment to start his own distillery. On Christmas day in 1887 the first whisky flowed from the still of the Glenfiddich distillery. Glenfiddich essentially created the Single Malt category in the 60’s and 70’s, often using ads that created a cult of personality of around the whisky and that of Sandy Grant Gordon, William’s great grandson. The company has always been incredibly savvy and it’s no wonder that they are the number one selling single malt in the world.

Ninety years later, on the opposite side of Scotland, another farmer was setting out to form his own legacy in a distinctly Scottish way: by quitting his job. William Grant had just quit his job as a bookkeeper at the Mortlach Distillery and purchased the land and equipment to start his own distillery. On Christmas day in 1887 the first whisky flowed from the still of the Glenfiddich distillery. Glenfiddich essentially created the Single Malt category in the 60’s and 70’s, often using ads that created a cult of personality of around the whisky and that of Sandy Grant Gordon, William’s great grandson. The company has always been incredibly savvy and it’s no wonder that they are the number one selling single malt in the world.