Awards are a fickle thing. Being the “best” is an arbitrary construct that essentially says that something followed the rules really well. Without a larger context the sentence “an Irish Whiskey wins best single malt in the world for the first time” doesn’t carry any meaning even if it is 100% factually accurate. Which it is.

In March of 2019 the World Whiskey Awards, presented by the thedrinksreport.com, announced the Teeling 24 Year Old Irish Single Malt whiskey as the Best Single Malt in the world. Much of the conversation after this announcement was how Ireland had won an upset victory over Scotland, the home of Malt Whisky. Especially since an Irish Whiskey had never won this award before.

But the World Whiskey Awards have only been handed out since 2012. Meaning there haven’t been many opportunities for an Irish Whiskey to make the list. Also, in 2014 the same awards selected a Taiwanese whiskey as the best single malt so there was already precedent for Scotland not being the top dog.

It’s easy to see the headlines as mere clickbait but there’s a deeper story. Ireland isn’t traditionally associated with Single Malt whiskey, for a wealth of historical reasons, so they’re not going to traditionally win single malt whiskey awards. And while Irish Single Malt has been made for centuries if anyone was going to win an award it was probably going to be the Teeling’s.

The Teeling family first got into the Irish Whiskey game in 1782 when Walter Teeling established a distillery on Dublin’s Marrowbone Lane, an epicenter of distilling at the time. This original distillery was eventually purchased by William Jameson & Co., cousins of the more famous John Jameson. This original distillery was shuttered in 1923 as economic woes began to systematically destroy the Irish Whiskey industry. In fact, by 1976 every single distillery in the city of Dublin had shut its doors. Then in 2015 Teeling reestablished itself in Market Square, not far from the family’s first distillery.

Now, if you’re paying attention you’re probably asking, “How does a four year old distillery win an award with a 24 year old whiskey?” and the answer reveals another layer.

The new Teeling Distillery was founded by John Teeling and his sons, descendants of good ol’ Walter, and it was not his first time starting new Irish Distillery. In 1985 John purchased an old industrial alcohol production plant in Cooley and began converting it to an actual whiskey distillery. It reopened in 1987 as the Cooley Distillery and was the first “new” distillery in Ireland in at least a decade.

Over the next several years the Cooley Distillery gained a reputation for quality and excellence in style. One of those being a distinctly Irish style of single malts. The Tyrconnell has always been one of my favorites, winning the International Wine and Spirits (IWSC) Gold Medal in 2004. They also gained a cult following with the Connemara, a peated Irish Single Malt, and the distillery quickly became a go to source for the slowly growing segment of drinkers looking for Irish Single Malt. After winning “Distillery of the Year” from the IWSC in 2008 and then the same award from Malt Advocate Magazine in 2010 the distillery was sold to Beam, now Beam Suntory, in 2011.

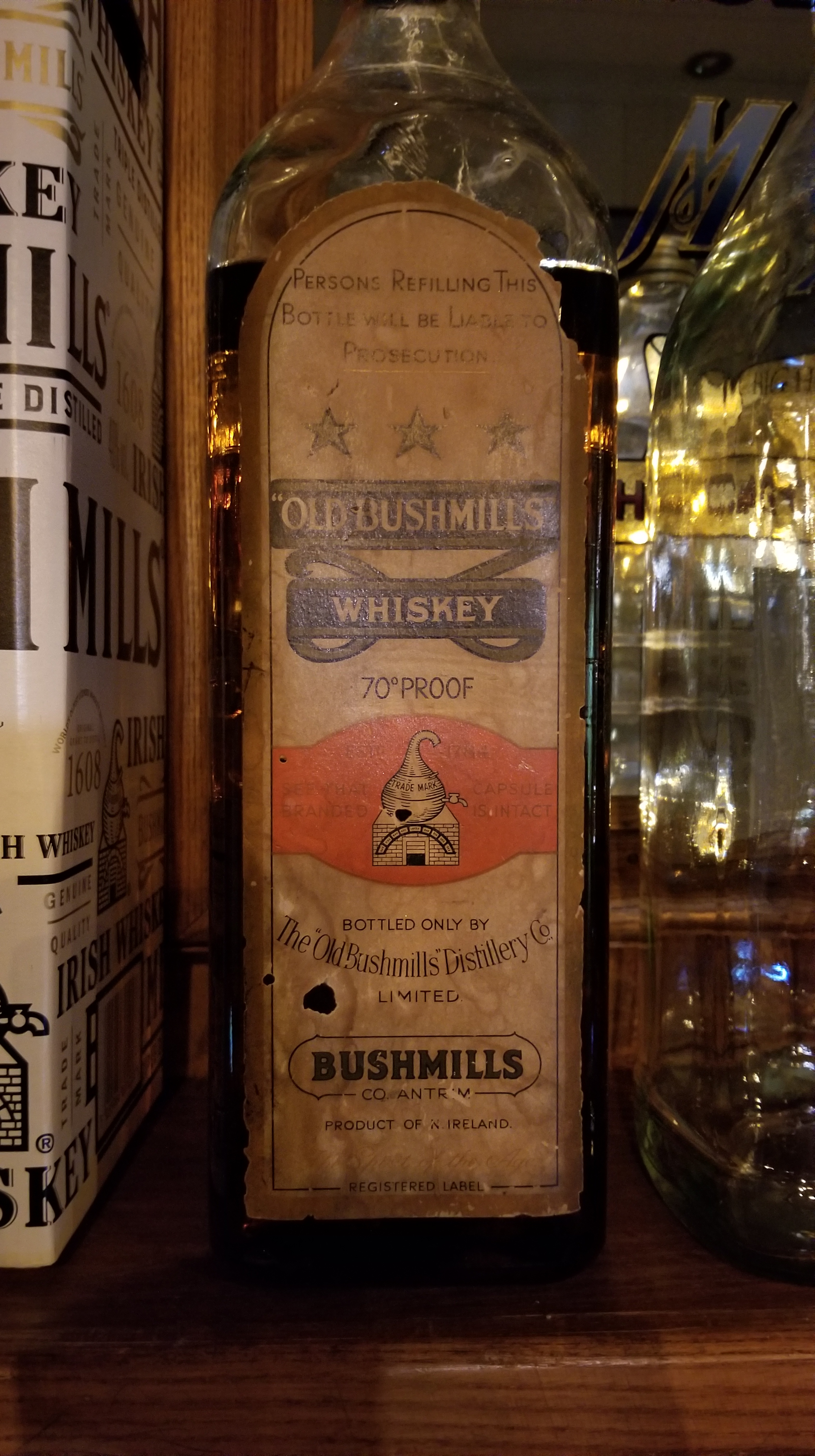

With all of this old Cooley whiskey I assumed that this bottle was old Cooley malt but after talking with people who know more about these things than I do it turns out that this is actually old Bushmill’s Single Malt.

As part of the sale Teeling kept 16,000 barrels worth of whiskey from Cooley and used that stock to establish the new Teeling brand in 2012, quickly followed by the new Dublin distillery three years later.

With all of this old Cooley whiskey I assumed that this bottle was old Cooley malt but after talking with people who know more about these things than I do it turns out that this is actually old Bushmill’s Single Malt. This adds yet another layer to the story as trying to pick apart who distilled, blended, aged, and otherwise had a hand in this whiskey over the years.

Here is a family, accustomed to winning awards winning another award on a whiskey that seems to have a foot in almost every part of the active Irish Whiskey world.

Whatever its providance the whiskey itself is a 24 Year Old Single Malt Irish Whiskey distilled in 1991. It was first aged in ex-Bourbon barrels before being married and further aged in ex-Sauternes casks. How much time it spent in each barrel type is unknown. Only 5000 bottles of 92 proof (46% ABV) non-chill filtered whiskey were produced, meaning that even if it wasn’t the best it’s still one of the rarest and oldest Irish whiskies on the market.

NOSE: Orange Zest, apricot, a slight nuttiness, and a bittersweet chocolate

PALETTE: Honey and malt, bright stone fruit, leather, caramel and a sprinkle of saltiness

FINISH: A long mellow finish that leans into the saltiness and the Sauterne finish

After all that, is this the best Single Malt in the world? I have absolutely no idea. It certainly falls into the rich flavors that I expect from old, indulgent malts yet it also presents a few flavor curve balls and is surprisingly alive which helps it stand out.

This is a malt that is relying on the past while building a future. It’s caught between multiple worlds and you can almost taste the journey it’s been on. Best may be a matter of opinion meant to generate buzz but the more I’ve learned about where this whiskey comes from the more interesting it’s become.

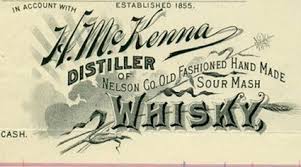

The whiskey produced at McKenna’s Nelson County distillery never carried the name ‘Bourbon’ but it was regarded to be of the highest quality. Newspaper at the time noted that McKenna never sold a drop that wasn’t at least three years old. There was even a bill introduced to Congress in 1892 asking for unlimited bond period on aging whiskey to prevent tax penalties on whiskey aging beyond the bond. This bill was known as “The McKenna Bill.” The next year McKenna passed away at the age of 75.

The whiskey produced at McKenna’s Nelson County distillery never carried the name ‘Bourbon’ but it was regarded to be of the highest quality. Newspaper at the time noted that McKenna never sold a drop that wasn’t at least three years old. There was even a bill introduced to Congress in 1892 asking for unlimited bond period on aging whiskey to prevent tax penalties on whiskey aging beyond the bond. This bill was known as “The McKenna Bill.” The next year McKenna passed away at the age of 75.