The Los Angeles Cocktail is terrible and is a perfect example of a bad drink that survives because it’s old.

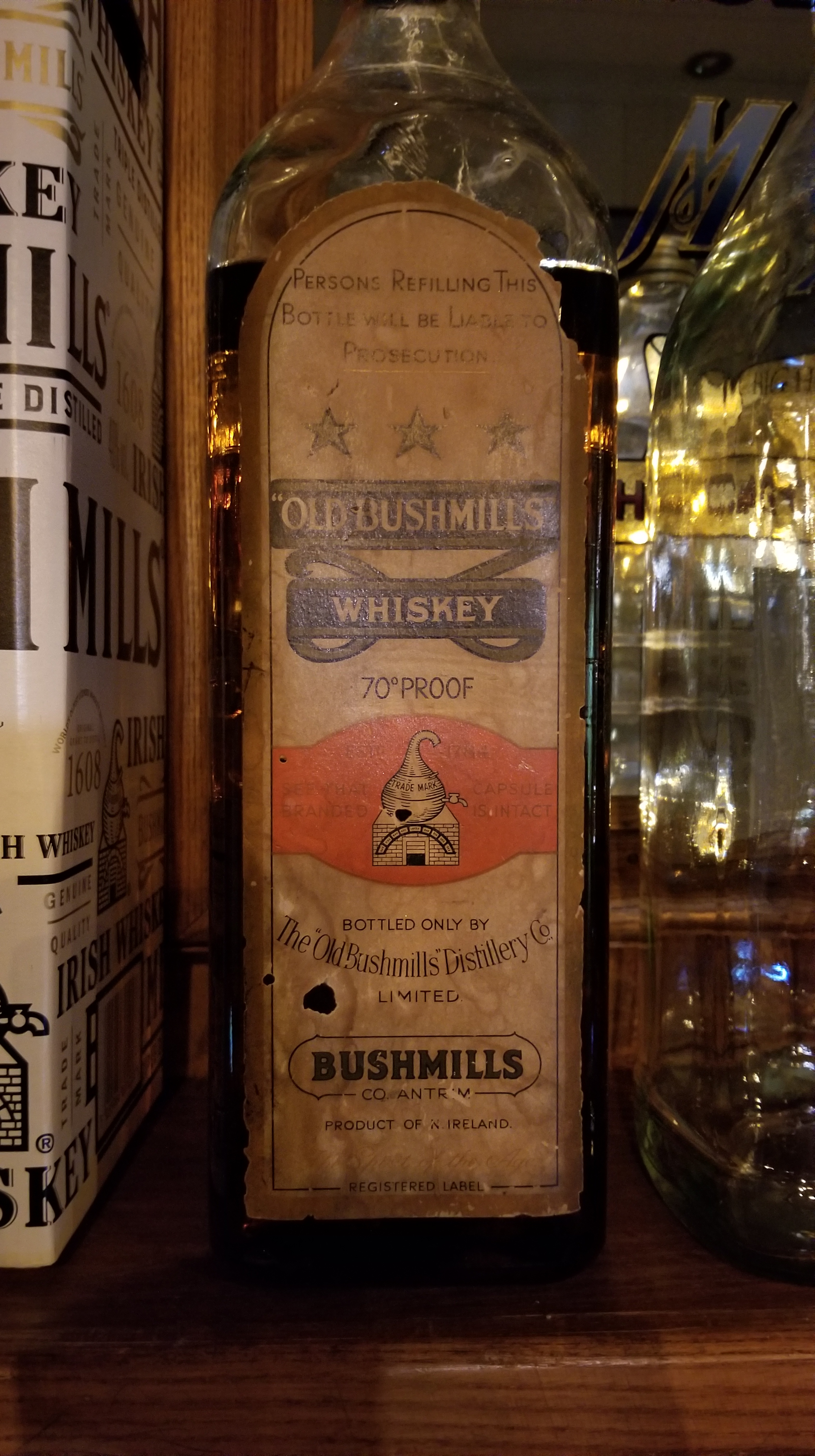

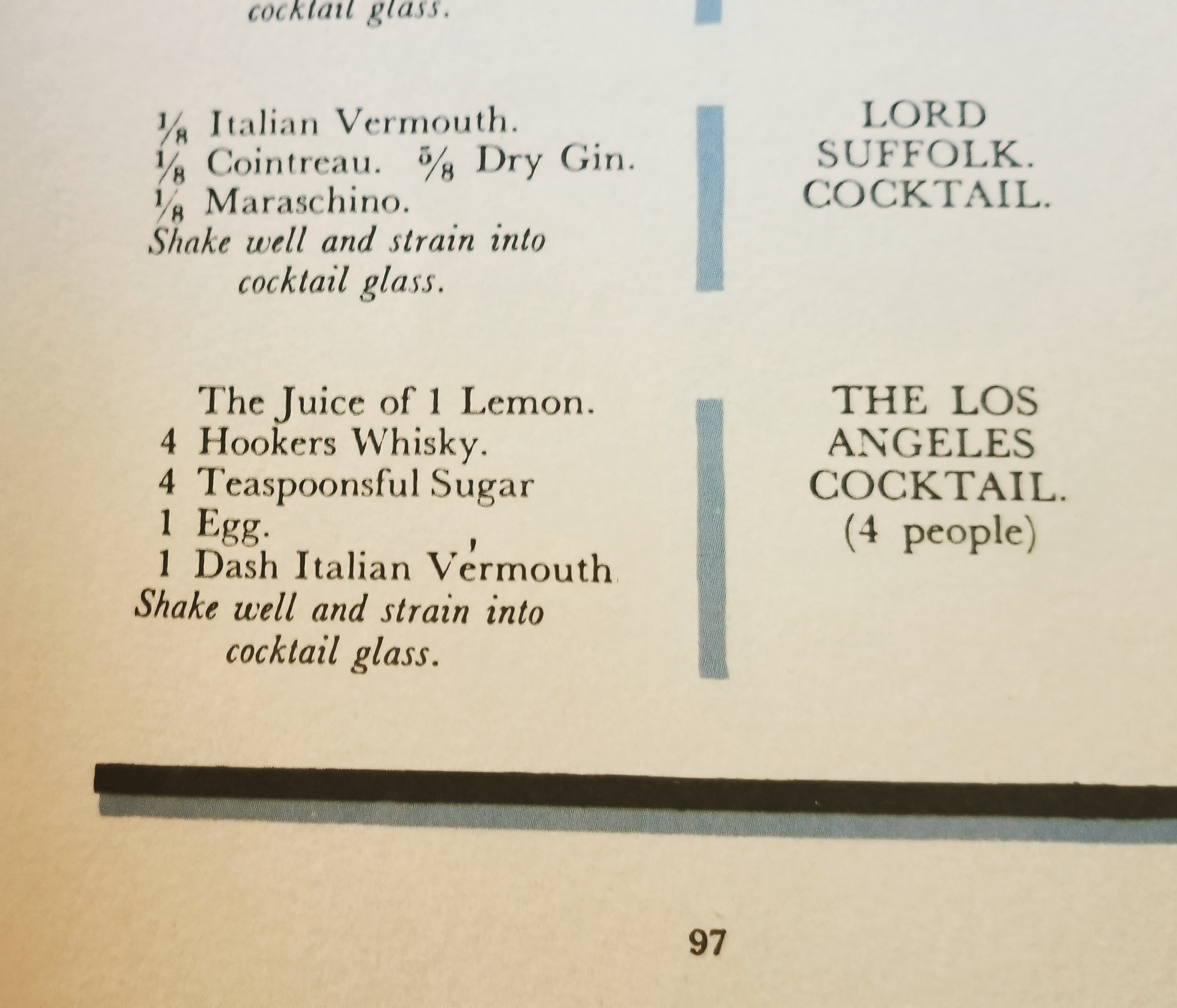

Buried within the pages of the Savoy Cocktail book, one of the quintessential drink tomes of the Golden and Modern cocktail age, is a drink that reads like a New Yorker describing their “totally real” visit to L.A. There are so many things that irritate me about this drink, the very first of which is that it’s not a damn cocktail!

Despite being listed alphabetically in the “cocktail” section there’s nothing about this drink that ties it to the traditional “cocktail” family of drinks. It contains no bitters and has enough citrus to dilute the base spirit beyond recognition. Apart from that the drink is described as serving four people, uses blended whiskey, powdered sugar, a whole egg, and only a “splash” of vermouth. It’s just a worse version of a New York Sour. While L.A. may have once been the subpar New York City that is certainly not the case any more and I think that’s what makes this drink stick in my craw.

There are so many little things that are off about this drink that it’s stuck in my head for years. I’ve lived in LA for a decade now and I feel like I’ve earned the right to call myself an Angeleno, so if a drink is going to be named after our city it should be damn good drink.

The first thing that I wanted to do to adapt this drink was scale it down. A drink designed for only four people is not efficient for service, though considering that L.A. often rolls twelve deep I can’t blame them for trying. Scaled down from four hookers (a measure of 2.5 ozs) to the standard 2 oz jigger of booze, a classic proportion of sour to sweet, and using an egg white instead of the whole egg creates a palatable, if completely forgettable, sour.

This adjusted recipe reads:

- 2oz Whiskey

- 1 oz Fresh Lemon Juice

- .75 oz Simple Syrup

- 1 Egg White

- 25 oz Vermouth

- Combine all ingredients in a mixing tin. Dry Shake. Shake With Ice. Double Strain.

The next sticking point is that there’s nothing about this drink that actually says “L.A.” And while the same can be said about the New York Sour, which may have actually originated in Chicago, if we’re going to improve a drink why not make it more representative? With this in mind the inoffensively mediocre powdered sugar was swapped out for a 50 brix Piloncillo syrup. Pilconcillo, or panela, is an unrefined, whole cane sugar typical of Latin America. It is made from the boiling and evaporation of sugar cane juice. It is commonly used in Mexico and has more flavor than brown sugar which is often white sugar with a little added molasses. This gives the drink a richer texture while also tying it into the Latino heritage of Los Angeles.

Next up was the spirit base. The richer piloncillo syrup completely overwhelmed lighter whiskies so I turned to my trusty baseline: Elijah Craig Straight Kentucky Bourbon. This added a delightful tannin and vanilla note but was not playing nice with the vermouth and lemon. So, I traded the vermouth for the recently reconstructed American version of Dubonnet Rouge. Served over a large rock with a float of the Dubonet the flavors were able to develop over time and the extra bitterness from the quina in the Dubonet helped tie the drink together. I actually used this drink for the regionals of the Heaven Hill Bartender of the Year competition this year and it’s absolutely delightful.

L.A. Sour:

- 1.5 oz Elijah Craig Small Batch

- .75 oz Piloncillo Syrup (50 Brix)

- .75 oz Fresh Lemon Juice

- 1 Egg White

- Dry Shake. Double Strain over one large ice cube.

- Float .75 oz Dubonnet Rouge

There’s no practical need to go further than this. The drink is delightfully crowd pleasing, recognizable, and recreateable. I highly recommend making this version of the drink yourself.I couldn’t set the drink down though. It kept burrowing through my brain begging for attention.

I have a natural disregard for “blended” whiskies. I find them light and forgettable but that doesn’t have to be the case. There are some beautiful blended malts and grain whiskies on the market, and not all of them are Japanese. So, I broke down the components and built up a house whiskey blend to complement the flavors.

It starts with an ounce of Bushmill’s 10 Year Single Malt. Irish Malt is lighter and fruiter than the more familiar Scotch malts while being more affordable than the Japanese counterparts. The Bushmills 10 also grants a solid barrel note and the vanilla that was coming from the Elijah Craig. Next, I wanted some spice and proof without overwhelming the delicate Irish malt so I added a half ounce of Old Overholt Bottled In Bond Rye. This added an oiliness, viscosity, and tannin that helped dry out the drink.

Finally, to lengthen out the blend, a half ounce of grain whiskey was added. The Nikka Coffey Grain would have worked wonderfully, but the pricing and recent announcement that it was being discontinued shut that experiment down. Though I have recently heard that it is only discontinued in Japan with plenty of stock in the U.S. remaining so it may be worth revisiting. In the mean time I headed back to the Emerald Isle where the Teeling Single Grain offered a compliment to both the Bushmill’s Malt and the Overholt Rye bite.

This house blend was delightfully robust but the Dubonnet, instead of being a unifying factor, was now coming across as thin, just like the vermouth in the original spec. The drink needed something richer while still maintaining that vermouth bitterness and acid. It needed to be concentrated. With that in mind I turned to my favorite toy, the rotovap. Running Dolin Rouge through the rotovap produced two wonderful products.

First a clear, concentrated vermouth flavored distillate. Second, a concentrated vermouth syrup that was left behind as the more volatile compounds were syphoned off. Both of these products are lovely, especially the syrup. However, I couldn’t imagine using this process to produce enough to maintain the volume of service that we do at NoMad LA so I went back to the drawing board.

With this concentrated Vermouth reduction as a benchmark we found that a traditional stove top reduction with 50% sugar by weight produced a vermouth syrup that was, as my father would say, “Good enough for government work.”

All the elements were now in place. Here was a drink that payed homage to its vintage roots, added in elements of the city it’s named for, and incorporated modern techniques, culinary thoughtfulness, and contemporary palettes and drinking styles. I’m also incredibly proud of the fact that this is the only drink I’ve ever put in front of our Bar Director Leo Robitschek that he had no tweaks for.

The Los Angeles Sour now reads on the menu at NoMad LA as:

- 1 oz Bushmill’s 10 Year Single Malt

- .5 oz Old Overholt Bottled In Bond Rye Whiskey

- .5 oz Teeling Single Grain Irish Whiskey

- .75 oz 50 Brix Piloncillo Syrup

- .75 oz Fresh Lemon Juice

- 1 Egg White

- Dry Shake. Shake with Kold Draft Ice. Double Strain over one large Ice Cube

- Float .75 oz Dolin Rouge Vermouth Reduction

I do have to admit I’m cheating for the sake of a story. Leo did have one critique. I originally pitched the drink with aquafaba, (a vegan egg white substitute made from beans), instead of egg white because lord knows L.A. loves its dietary restrictions. Both versions of the drink past muster but the egg white variation felt more robust. But because of this original thematic pitch, and aa cheeky nod to L.A. drinkers, the Los Angeles Sour will always available “vegan upon request.”