With all the excitement, food, and celebrations that are crammed into the space between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day you can be excused for not noticing that noted scoundrel and always bartender Jeffrey Morgenthaler managed to squeeze a completely new holiday in there: December 5th, Repeal Day.

Repeal Day is the Hallmark Card Holiday of the booze world.

Repeal Day marks the anniversary of the passing of the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on December 5th, 1933. The 21st Amendment acknowledged that the previous 13 years of alcohol prohibition were in fact a terrible idea. It reinstated the constitutional right of every man and woman (of legal drinking age) in these United States to raise a glass in celebration, in mourning, or simply because its Happy Hour damn it. Wander into any “serious” cocktail bar on December 5th and odds are you’ll find a whole Repeal Day cocktail menu.

But here’s the thing, Repeal Day is the Hallmark Card Holiday of the booze world.

Hindsight, even when drinking, is still 20/20. Through the lens of history it is easy to see that Prohibition was an outright failure but its repeal brought its own host of issues that still reverberate 85 years later.

According to proponents like Molly Hatchet, Prohibition was going to reduce drinking, reduce domestic violence against women and children, reduce crime AND cut government spending. That’s a tall glass that never got filled.

Spending, taxes, and crime, especially organized crime, all took an uptick. People actively flaunted their lawlessness to the point that a wealthy Prohibitionist by the name of Delcevare King sponsored a contest to create an appropriate word to describe these “lawless drinkers.” The winning word was independently submitted by two different people and the term Scofflaw was born followed shortly thereafter by a mixed drink of the same name.

Prohibition broke bartending…And then even worse for the profession of bartending, Prohibition ended.

Prohibition also indirectly gave birth the Federal Income Tax. Before Prohibition 30-40% of the Federal budget was generated from taxes on alcohol. A Federal Income Tax was technically un-Constitutional and needed a Constitutional Amendment to make it legal. The 16th Amendment legalizing the Federal Income tax was passed in 1913 with direct help from Prohibitionists.

I also feel like it caused a cultural disconnect. Every civilization has learned to ferment and distill eventually developed their own native spirit and their own drinking traditions to go with that spirit. These traditions are passed from parent to child and a respect for alcohol becomes a part of everyday life. Prohibition pushed alcohol into the dark, demonized it yet also made in alluring. You can still see this destructive relationship play out in our modern binge drinking habits.

On the other hand, we are a nation of immigrants. A hodgepodge, mish mash of different cultures and booze. Maybe Prohibition just sped up the naturally occurring separation. The Italians know how to drink amaro, the French know how to drink brandy, and the Scandinavians know how to drink aquavit but what the hell does the English colonist do with any of those? The art of mixing drinks is a distinctly American art and I’ve always believed it had it’s roots in the Irish barman having no idea what to do with the Dutch Genever and the French Vermouth so fuck it, let’s mix it together until it’s delicious.

Which leads naturally into Prohibitions effect on the craft of tending bar. Prohibition broke bartending. While popular culture glorifies the idea of the speakeasy and the great mixed drinks of Prohibition the truth was that while people drank gallons at speakeasies what they drank was terrible.

Before Prohibition bartending was a skilled and respected trade. Bartenders would apprentice and learn their craft just like any other skilled tradesman. Now and entire profession was made illegal and those that knew how to bartend moved overseas and taught the rest of the world how to mix drinks.

For 13 years the trade languished with no one to train the next generation and basic skills and knowledge was lost. And then even worse for the profession of bartending, Prohibition ended.

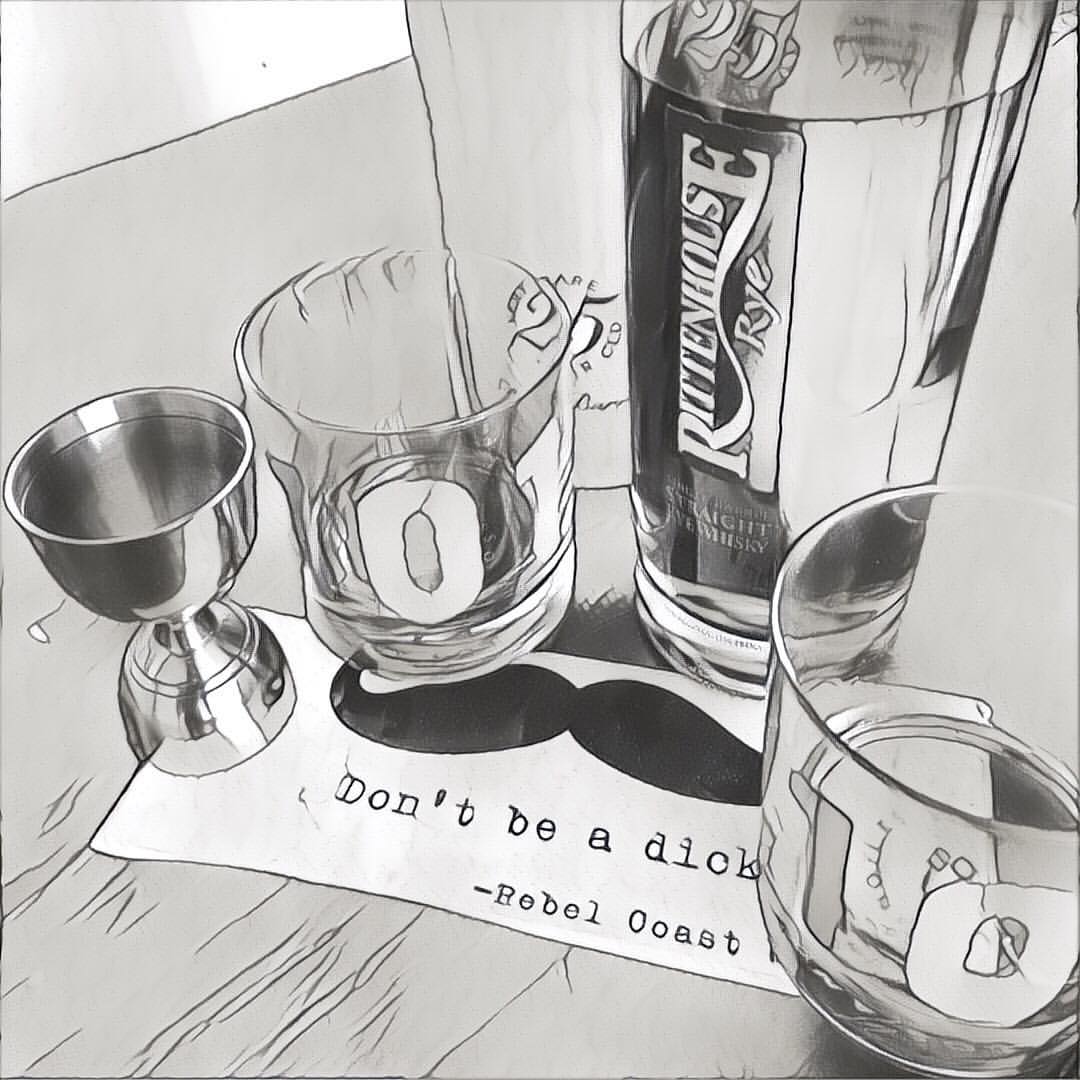

Scofflaw:

2 oz Rye Whiskey

.5 oz Dry Vermouth

.5 oz Grenadine

.5 oz Lemon

2 Dash Orange Bitters.

Shake with Ice, Double strain into a Sour Glass

The moment selling booze was legal again everyone wanted to open a bar, which means you need bartenders. The old skilled tradesman had moved on. There were no young professionals so it became a job for amateurs. The end of Prohibition was arguably the worse thing that could have happened to the American “mixology” tradition. 80+ years later and the professionalism that was taken for granted is still viewed as aloof or fussy today.

And all of this is before we even get into the how the disruption in alcohol production eventually to lead watered down, blended whiskies and eventually the rise of gin and then vodka over the US’s own native spirit: Bourbon. A cascade effect that changed how an entire culture drank. Prohibition and the compromises that needed to be made to for its repeal still shape how, where, and what we drink to this day. (Not to mention the abhorrent three-tiered system.)

Yet, because of Repeal Day I’ve had steady, good employment for most of my adult life and have gotten to travel the world all because I can but booze in a glass in a way that makes other people want to drink it.

So, should we be celebrating? Absolutely. But when you find yourself saddled up to the bar this December 5th ask yourself, are you celebrating some mythological golden age through boozed tinted glasses? Or are you celebrating the triumph of personal freedom and rational thinking? Either way, once you’re done with the inevitable brand-sponsored Old Fashioned throw the barkeep a curve ball and see how good a Scofflaw they can make.

Next is added a few short dashes of bitters. Bitter is an interesting flavor. Science still debates why exactly we taste bitter but the general consensus is that we evolved the capacity as a way to detect poisonous plants. This is also why a little bitter goes such a long way. Our brains are hardwired to recognize the bitter before anything else. It doesn’t matter how mouthwatering delicious something is if it’s going to ultimately kill you. Now couple this with the fact that pure alcohol is actually poison but doesn’t actually taste like anything. What we often recognize as “alcohol” is really just the upfront burn. This touch of bitter is a stage magician. We’re so focused on the bitter that we don’t notice the alcoholic burn that it just slipped past our taste buds.

Next is added a few short dashes of bitters. Bitter is an interesting flavor. Science still debates why exactly we taste bitter but the general consensus is that we evolved the capacity as a way to detect poisonous plants. This is also why a little bitter goes such a long way. Our brains are hardwired to recognize the bitter before anything else. It doesn’t matter how mouthwatering delicious something is if it’s going to ultimately kill you. Now couple this with the fact that pure alcohol is actually poison but doesn’t actually taste like anything. What we often recognize as “alcohol” is really just the upfront burn. This touch of bitter is a stage magician. We’re so focused on the bitter that we don’t notice the alcoholic burn that it just slipped past our taste buds.

Next up is dilution. While alcohol itself has no flavor it acts as a great transport for flavor. Ethanol caries those flavors molecules in a magical solution but it keeps them locked up tightly. A little dilution opens those locks and lets the heart, the true flavor burst through.

Next up is dilution. While alcohol itself has no flavor it acts as a great transport for flavor. Ethanol caries those flavors molecules in a magical solution but it keeps them locked up tightly. A little dilution opens those locks and lets the heart, the true flavor burst through.