Spontaneity is not my strong suit.

Example A: my girlfriend swears by the deals emailed out daily by Scott’s Cheap Flights. Yet every time a deal lands, I have to ask about time frame, logistics, check on available vacation days, and generally stressed about the fact that booking this trip means that we won’t be able to book some other hypothetical trip that doesn’t yet exist and just like that the deal, and the moment, is gone.

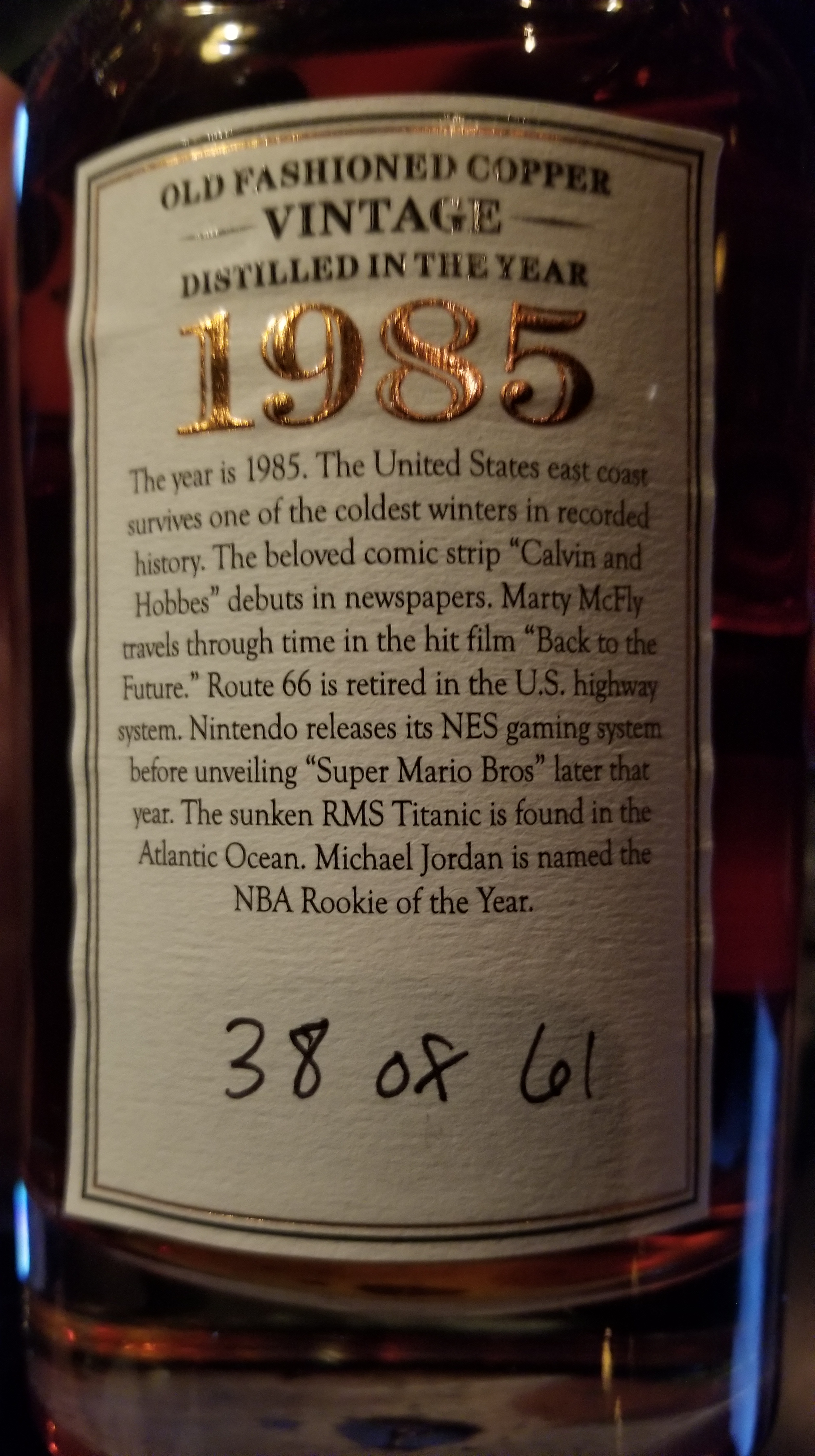

Example B: We received a bottle of the O.F.C 1985 Vintage Bourbon a year ago and I’ve been planning to write about it ever since. So, what the hell is O.F.C. and why has it been on my mind for literally a year?

O.F.C. stands for Old Fashioned Copper and is the original name for the distillery founded by Col. E.H Taylor in 1869. Col. Taylor was an expert marketer and helped establish the concept of a Bourbon “brand” as well as being one of the major figures behind the passing of the Bottled In Bond act of 1897.

The distillery itself was sold to another legend, George T. Stagg, in 1878. There’s an apocryphal story that one of the conditions of the sale was that Stagg could keep the initials O.F.C. but he had to change at least one of the words it stood. This is why the distillery is sometimes called the “Old Fire Copper” distillery. Regardless of the veracity of this claim the distillery’s name was officially changed to the George T. Stagg Distillery in 1904. It was the first distillery to utilize climate-controlled aging warehouses when Stagg installed steam heaters in 1886 and was one of only four Kentucky Distilleries granted a license to continue distilling throughout Prohibition.

The distillery changed hands a few more times in the 20th century before finally being purchased by the Sazerac Corporation in 1992 and its named changed once again. Now known as Buffalo Trace it arguably produces some of the most sought after American Whiskey on the market, including bottles named after both Taylor and Stagg as well as the much desired Pappy Van Winkle line.

The distillery clearly has experience with special releases but even amongst the plethora of rare bottles the O.F.C. stands out.

The O.F.C. is less a special release and more of a time capsule. These are all single barrel, vintage dated Bourbons. Each bottle is sourced from a single barrel and marked with the year of distillation. This makes each vintage completely unique with the mashbill and age varying depending on the bottling. Another intriguing fact is that this line up was originally produced only for charity.

The team at Sazerac and Buffalo Trace are just as savvy marketers as Col. Taylor was back in the day. I have to imagine that when they see bottles of their whiskey selling for thousands of dollars on the secondary market that they looked for a way to capitalize on that market value yet still offer an added bonus. The original three releases were only made available to 200 charities, at no cost, to auction off and help raise money for their cause. It was a great way to turn the image of limited whiskey auctions on its head and raise $1.2 million dollars for charity. It also immediately established the O.F.C. line as a super limited, ultra premium bottle. I was silently jealous of the fact that I would never see one of these bottles yet still applauded the move to raise money for worthy causes. But when the second round of releases was made available for retail purchase I leapt at the opportunity. Especially with the vintage being offered was the 1985. It’s not often you have a shared birth year for your whiskey.

The 1985 Vintage is one of only 61 bottles to come from a barrel which was stored on the second floor of Warehouse Q. Buffalo Trace says that all of the barrels were tasted over time and removed from the barrel before becoming over oaked and since there is no age statement listed on the bottle it’s hard to tell the precise age of the bottle. This isn’t an uncommon practice, Buffalo Trace has done similar things with Eagle Rare 17 and Sazerac 18 so the whiskey isn’t as much as an oak bomb as you might expect. It is certainly old but there’s no official word on if it was a full 33 years in oak before being bottled. With that in mind let’s dive into the glass:

NOSE: Rich oak, Dried fruit, and vanilla

PALATTE: Rich vanilla, dark cherry, prune, oak, and a dark earthiness

FINISH: Bitter chocolate, a touch of tobacco, and a coating lingering sense of time

Overall this is an excellent example of old American Bourbon whiskey. It is still alive without being over oaked and has a power of flavor to match up to the power of the years it spent asleep in the barrel. The issue, as always, is the price. The bottle comes in at a staggering suggested retail price of $2,500. When the proceeds were going to charity this number wouldn’t have raised peep from me but now it changes the talking points.

Is this good whiskey? Yes. Is it for everyone? Absolutely not. It is a special occasion, made so by the fact that it is a living time capsule. You are paying for the time and history as much as the whiskey itself. I will argue that experiences are more important than money but the value is certainly subjective. I for one am going to savor the fact that I get to experience this bottled moment of time and not take it for granted.

college not because it was phenomenal stuff, but because it was affordable. I moved on as a slight increase in disposable income allowed me to try other things yet here I am unabashedly keeping it in a decanter of honor on my back bar. And I’m not the only one, Ancient Age has a massive cult following for its affordability and quality, at least its quality in comparison to its price. But why?

college not because it was phenomenal stuff, but because it was affordable. I moved on as a slight increase in disposable income allowed me to try other things yet here I am unabashedly keeping it in a decanter of honor on my back bar. And I’m not the only one, Ancient Age has a massive cult following for its affordability and quality, at least its quality in comparison to its price. But why?

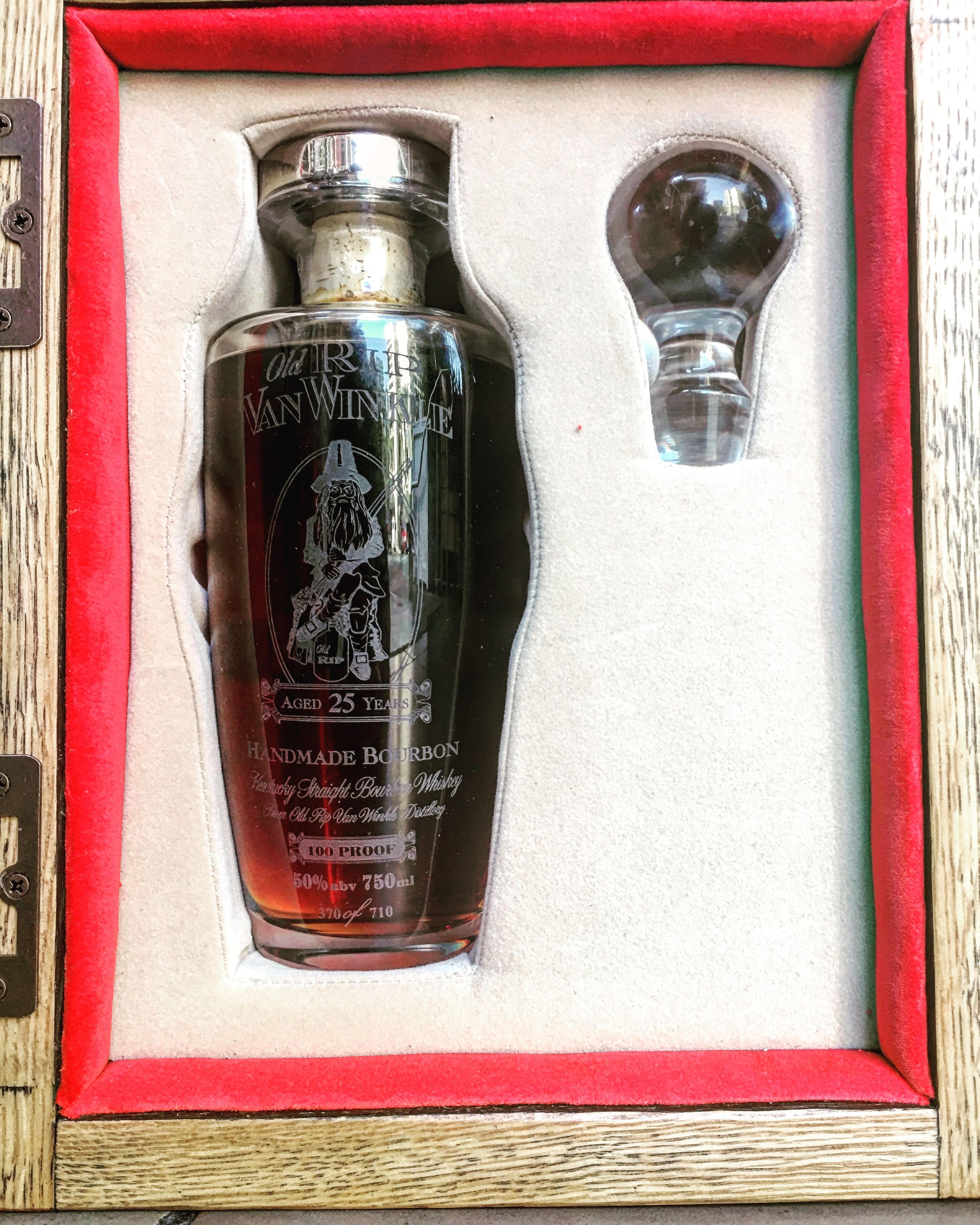

25 years old and 100 proof this Bourbon carries serious weight. The nose is of dried oak, dark coffee, and just a touch of stone fruit. The finish is almost nonexistent but it doesn’t matter because the mid-palette travels for hours. White pepper, caramelized oranges, deep ripe cherry, of course a vanilla and caramel note but what’s interesting is how well this walks the line massive oak flavor without being over oaked. Right when I was expecting it to dive into wet wood and raisins it instead let the pepper burn for another moment before evaporating completely on the tongue. This whiskey is better aged than the standard 23, and I’d say it’s at least as lively as the 20 year old.

25 years old and 100 proof this Bourbon carries serious weight. The nose is of dried oak, dark coffee, and just a touch of stone fruit. The finish is almost nonexistent but it doesn’t matter because the mid-palette travels for hours. White pepper, caramelized oranges, deep ripe cherry, of course a vanilla and caramel note but what’s interesting is how well this walks the line massive oak flavor without being over oaked. Right when I was expecting it to dive into wet wood and raisins it instead let the pepper burn for another moment before evaporating completely on the tongue. This whiskey is better aged than the standard 23, and I’d say it’s at least as lively as the 20 year old.

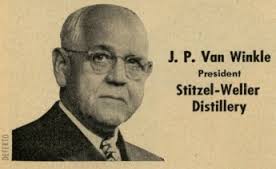

Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle was a real man. He was involved in the whiskey business well before prohibition. He and his partner, Alex Farnsley purchased a controlling stake in W.L. Weller and Sons in 1908. At the time Weller and sons was strictly a bottler. They distilled nothing themselves but worked very closely with the Stitzel Distillery.

Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle was a real man. He was involved in the whiskey business well before prohibition. He and his partner, Alex Farnsley purchased a controlling stake in W.L. Weller and Sons in 1908. At the time Weller and sons was strictly a bottler. They distilled nothing themselves but worked very closely with the Stitzel Distillery. Pappy’s flagship brand was Old Fitzgerald. His biggest contribution to his namesake Bourbons is his “whisper of wheat.” Every brand that came out of Stizel-Weller was a “Wheated” Bourbon as opposed to the standard mash of corn, rye, and barley. To many this produces a rounder, softer bourbon with more dark fruit and cherry.

Pappy’s flagship brand was Old Fitzgerald. His biggest contribution to his namesake Bourbons is his “whisper of wheat.” Every brand that came out of Stizel-Weller was a “Wheated” Bourbon as opposed to the standard mash of corn, rye, and barley. To many this produces a rounder, softer bourbon with more dark fruit and cherry.

In the end, the cold hard fact about why Pappy Van Winkle is considered the best Bourbon in the world is because people keep saying it is. And because people keep making money off of saying it is. Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Think about that the next time you see it listed on someone’s menu for $150+ a pour, and maybe find a bartender you trust to help you drink your next history lesson.

In the end, the cold hard fact about why Pappy Van Winkle is considered the best Bourbon in the world is because people keep saying it is. And because people keep making money off of saying it is. Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Think about that the next time you see it listed on someone’s menu for $150+ a pour, and maybe find a bartender you trust to help you drink your next history lesson.