Pappy Mania has struck early this year and for the first time in years even I’m feeling a bit of hype.

The early onset of this yearly bourbon malady is the amazing limited release of an Old Rip Van Winkle 25 Year Old Kentucky Straight Bourbon. What makes it hype worthy is that fact that like the A.H. Hirsch 16 Year Special Reserve this bottle is a piece of history. A gussied up, fancy decanter of liquid history.

My feelings on Pappy and the bottle hunting that surrounds it are pretty well documented, but unlike the yearly release of what you could now call the standard Van Winkle’s this bottle is something different. This is actual Stitzel-Weller Bourbon.

Distilled in the Spring and Fall of 1989, the 11 barrels that comprise this release were aged on the lower floors of the metal clad warehouses at Stitzel-Weller that shut

down in 1992. But just because the distillery stopped making spirit doesn’t mean the whiskey stopped aging. Leftover stocks continued to rest at the warehouse with some being sold off and some being bottled for various brands but these barrels stayed in the family. In 2002 they were transferred to Buffalo Trace where they aged for another 12 years on the lower floors of one of Buffalo Traces brick warehouses. In 2014 the whiskey was dumped into steel tanks. This isn’t an uncommon practice with older whiskies, the past few releases of Sazerac 18 Year Old Rye have been steel tanked, and it simply halts the oak aging process. Oxidation can still happen but this is certainly not an aging experiment, nor can it legally be considered aged in steel tanks. It is simply an attempt to keep the whiskey from becoming over oaked and undrinkable.

So what were they doing with the whiskey for the next 2.5 years? They were figuring out how to sell it. Whiskey this old is a massive expense in time, labor, and lost product so it needs to have an appropriate price tag, but you also need to convince people that it’s worth the price tag. It doesn’t seem like that would be a problem with a bottle of Pappy Van Winkle but they pulled out all the stops for this release.

The massive box each of the 710 bottles comes in is made out of the oak staves from the 11 barrels the whiskey aged in. The Glencairn Crystal Studio designed a bespoke decanter, every bottle is signed by Julian Van Winkle, III and it comes with a parchment sheet with the short version of the whisky’s story. It’s a production.

At a mere 710 bottles, the secondary market for this bottle is literally drooling. But what’s interesting to me is that Buffalo Trace, and the Van Winkles, seem to be making steps to try and curb the flipping of this bottle. From what I’m told 9 bottles hit Los Angeles with maybe 30 for the whole state of California. But not a single bottle of those went to an Off Premise Liquor store. Every bottle was sent to a bar, with each bottle number being carefully recorded so that if a bottle does emerge on the Secondary Market they’ll be able to track it back to its source and supposedly punish the seller. While I appreciate the attempt to keep the bottles from becoming mere commodity trading with the secondary market already willing to pay $15,000 I can’t see these bottles actually staying on the shelves of all the bars they were allocated to.

But that’s the story ABOUT the whiskey, what about the whiskey itself? Bottled at  25 years old and 100 proof this Bourbon carries serious weight. The nose is of dried oak, dark coffee, and just a touch of stone fruit. The finish is almost nonexistent but it doesn’t matter because the mid-palette travels for hours. White pepper, caramelized oranges, deep ripe cherry, of course a vanilla and caramel note but what’s interesting is how well this walks the line massive oak flavor without being over oaked. Right when I was expecting it to dive into wet wood and raisins it instead let the pepper burn for another moment before evaporating completely on the tongue. This whiskey is better aged than the standard 23, and I’d say it’s at least as lively as the 20 year old.

25 years old and 100 proof this Bourbon carries serious weight. The nose is of dried oak, dark coffee, and just a touch of stone fruit. The finish is almost nonexistent but it doesn’t matter because the mid-palette travels for hours. White pepper, caramelized oranges, deep ripe cherry, of course a vanilla and caramel note but what’s interesting is how well this walks the line massive oak flavor without being over oaked. Right when I was expecting it to dive into wet wood and raisins it instead let the pepper burn for another moment before evaporating completely on the tongue. This whiskey is better aged than the standard 23, and I’d say it’s at least as lively as the 20 year old.

I think bottling at 100 proof made a huge difference on the final product. The burn and the massive presence of the mid-palette flavors solved almost all of the complaints I had with the Old Fitzgerald 20 Year Old, which was also Stitzel-Weller whiskey that finished it’s aging at Heaven Hill. There were 12 barrels for that release and the finish was also nonexistent but in comparison the Old Fitz just seemed flabbier. Those extra proof points and the Van Winkle name come with a much heftier price tag though.

In the end, it’s hard for me to separate the whiskey from the history. When I pick up this bottle, when I sell this bottle at the bar, when I manage to sneak a sip of this bottle it’s not the whiskey I’m talking about. It’s the history. The liquid time that is carried over the tongue adds volumes to the value but is it enough added value? I’m not sure, but for the first time in a long time I find myself agreeing with a massive price tag on a massive whiskey. At least at the retail level. But if you have a spare $15,000 hanging around I know someone who might be accepting bribes…

The single barrel offerings are at a solid 90 proof, one of the things that set them apart from the standard bottles, but the color scheme on the new label is an almost complete palate swap. Where the normal Whiskey Row bottles harken back to the old white/cream style labels of the brands history the new single barrel is jet black with silver lettering. And clearly looking to scratch the whiskey intelligentsia’s need to know everything the rickhouse and floor where the barrel aged are large and center.

The single barrel offerings are at a solid 90 proof, one of the things that set them apart from the standard bottles, but the color scheme on the new label is an almost complete palate swap. Where the normal Whiskey Row bottles harken back to the old white/cream style labels of the brands history the new single barrel is jet black with silver lettering. And clearly looking to scratch the whiskey intelligentsia’s need to know everything the rickhouse and floor where the barrel aged are large and center.

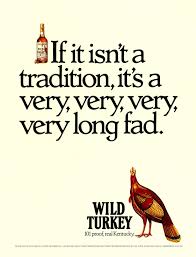

y as a brand was said to originate in the 1940’s when an Austin Nichols executive, Thomas McCarthy, brought some choice whiskey along on a wild turkey hunting trip in South Carolina. Enamored with the samples he brought his friends kept asking for more of “that wild turkey bourbon.” More likely it was a marketing approach to appeal to hunters and the rugged, rustic type but every whiskey loves a mythical origin story.

y as a brand was said to originate in the 1940’s when an Austin Nichols executive, Thomas McCarthy, brought some choice whiskey along on a wild turkey hunting trip in South Carolina. Enamored with the samples he brought his friends kept asking for more of “that wild turkey bourbon.” More likely it was a marketing approach to appeal to hunters and the rugged, rustic type but every whiskey loves a mythical origin story.

The whiskey produced at McKenna’s Nelson County distillery never carried the name ‘Bourbon’ but it was regarded to be of the highest quality. Newspaper at the time noted that McKenna never sold a drop that wasn’t at least three years old. There was even a bill introduced to Congress in 1892 asking for unlimited bond period on aging whiskey to prevent tax penalties on whiskey aging beyond the bond. This bill was known as “The McKenna Bill.” The next year McKenna passed away at the age of 75.

The whiskey produced at McKenna’s Nelson County distillery never carried the name ‘Bourbon’ but it was regarded to be of the highest quality. Newspaper at the time noted that McKenna never sold a drop that wasn’t at least three years old. There was even a bill introduced to Congress in 1892 asking for unlimited bond period on aging whiskey to prevent tax penalties on whiskey aging beyond the bond. This bill was known as “The McKenna Bill.” The next year McKenna passed away at the age of 75.

But in a world of vanishing age statements and soaring prices I feel it’s hard for the general consumer to not see this as a replacement of a beloved bottle by a younger whiskey at a higher price. That’s not a problem with the Harmony though. That’s just the reality of the whiskey world we now live in.

But in a world of vanishing age statements and soaring prices I feel it’s hard for the general consumer to not see this as a replacement of a beloved bottle by a younger whiskey at a higher price. That’s not a problem with the Harmony though. That’s just the reality of the whiskey world we now live in.

nown as the Boulevard Distillery) in 1971 and renamed it the Wild Turkey Distillery. This purchase made sense since the Ripy distillery was where most of the Wild Turkey Whiskey was coming from but it was terrible timing as “white goods” started gaining steam and the bourbon market tanked. The brand and distillery, were purchased by Pernod Ricard in 1980 and then sold to Gruppo Campari in 2009. But through out all of those changes Jimmy Russell has been there, making whiskey.

nown as the Boulevard Distillery) in 1971 and renamed it the Wild Turkey Distillery. This purchase made sense since the Ripy distillery was where most of the Wild Turkey Whiskey was coming from but it was terrible timing as “white goods” started gaining steam and the bourbon market tanked. The brand and distillery, were purchased by Pernod Ricard in 1980 and then sold to Gruppo Campari in 2009. But through out all of those changes Jimmy Russell has been there, making whiskey.

ake anymore? Seeing the Wild Turkey 101 Rye return with a vengeance was transcendent moment amidst all of these brands lowering proof and dropping age statements. Yet for all of my love of Jimmy, and his rye, when I drink the Bourbon it’s usually me trying to figure out why I don’t drink the Bourbon.

ake anymore? Seeing the Wild Turkey 101 Rye return with a vengeance was transcendent moment amidst all of these brands lowering proof and dropping age statements. Yet for all of my love of Jimmy, and his rye, when I drink the Bourbon it’s usually me trying to figure out why I don’t drink the Bourbon.

Let me explain. Despite not carrying standard Woodford I’ve always been interested in the Master’s Collection (and the rye but that’s a story for another time). The Master’s Collection is an ongoing series that first began in 2005. It is a once a year release that is always something experimental. It doesn’t always qualify as a bourbon, the mashbill might not meet the required limits or the barrel finishes might be outside the strict bourbon law, but they are always ambitious. And more interestingly they are supposedly whiskey produced only from the pot stills at the prime Woodford Distillery in Versailles, KY.

Let me explain. Despite not carrying standard Woodford I’ve always been interested in the Master’s Collection (and the rye but that’s a story for another time). The Master’s Collection is an ongoing series that first began in 2005. It is a once a year release that is always something experimental. It doesn’t always qualify as a bourbon, the mashbill might not meet the required limits or the barrel finishes might be outside the strict bourbon law, but they are always ambitious. And more interestingly they are supposedly whiskey produced only from the pot stills at the prime Woodford Distillery in Versailles, KY. I’m in love with the idea of all of these yet on the actual liquid hasn’t always lived up to those expectations. But those expectations aren’t always fair. The Woodford name can sometimes influence what you expect to be tasting. For instance, Brown-Forman used to distill the Rittenhouse Rye for Heaven Hill while their production was limited due to a distillery fire in the 90’s. Yet once Heaven Hill moved production back to their own distillery and Woodford released a rye that is pretty obviously a continuation of that Rittenhouse heritage I judged it more harshly simply because of that Woodford name.

I’m in love with the idea of all of these yet on the actual liquid hasn’t always lived up to those expectations. But those expectations aren’t always fair. The Woodford name can sometimes influence what you expect to be tasting. For instance, Brown-Forman used to distill the Rittenhouse Rye for Heaven Hill while their production was limited due to a distillery fire in the 90’s. Yet once Heaven Hill moved production back to their own distillery and Woodford released a rye that is pretty obviously a continuation of that Rittenhouse heritage I judged it more harshly simply because of that Woodford name.

In distilling history isn’t a simple straight line from the old school pot stills to the modern industrial column/continuous stills used in most major distilleries today. One of the most notable

In distilling history isn’t a simple straight line from the old school pot stills to the modern industrial column/continuous stills used in most major distilleries today. One of the most notable

Their standard barrel entry proof

Their standard barrel entry proof

Named after the stream that ran along Abraham Lincoln’s childhood home in Kentucky, the bottle was modeled after turn of the century apothecary bottles with the label inspired by the tradition of wrapping bottles in newspaper at the distillery. Knob Creek was originally an age stated 9 Year Old bourbon bottled at 100 proof. The age statement has been dropped in the past few years but the brand still claims extra aging compared to the companies other small batch whiskies. So in this case pre-Prohibition style would seem to mean longer aged and higher proof, which is almost the exact opposite of what those early whiskies would have been.

Named after the stream that ran along Abraham Lincoln’s childhood home in Kentucky, the bottle was modeled after turn of the century apothecary bottles with the label inspired by the tradition of wrapping bottles in newspaper at the distillery. Knob Creek was originally an age stated 9 Year Old bourbon bottled at 100 proof. The age statement has been dropped in the past few years but the brand still claims extra aging compared to the companies other small batch whiskies. So in this case pre-Prohibition style would seem to mean longer aged and higher proof, which is almost the exact opposite of what those early whiskies would have been. What set the Booker’s Rye apart was the age and a unique mashbill. The Knob Creek 2001 certainly has the age, at 14 years old it clocks in a good five years older than the old 9 year, but there’s no variation on the mashbill, simply different batches. This leaves a through line connecting it to the standard issue Knob Creek because no matter what batch you pick up all of these bottles are unmistakably Knob Creek: powerful, with pistachio, walnut, sweet oak and that unmistakable Jim Beam yeast.

What set the Booker’s Rye apart was the age and a unique mashbill. The Knob Creek 2001 certainly has the age, at 14 years old it clocks in a good five years older than the old 9 year, but there’s no variation on the mashbill, simply different batches. This leaves a through line connecting it to the standard issue Knob Creek because no matter what batch you pick up all of these bottles are unmistakably Knob Creek: powerful, with pistachio, walnut, sweet oak and that unmistakable Jim Beam yeast.